To continue highlighting 25 artifacts from within our collections for our 25th anniversary, this week we are featuring emergency postcards that were printed and distributed by the Canadian Post Office during the Cold War.

The Canadian Post Office, now known as Canada Post, printed Emergency Change of Address and Safety Notification Postcards in the 1960s during a critical time in world history. These postcards were distributed to regional post offices with the purpose of being a civil defence measure, enacted by the Canadian government to protect civilians during times of turmoil. This function of government dealt with plans, preparations, and organizations for emergency situations that may have arisen from wars or peacetime disasters to ensure the survival of the population.

To prepare Canadians for potential disaster during the Cold War, the Government of Canada held a 24-hour emergency preparedness drill from November 13 to November 14, 1961. This nationwide drill, led by the Canadian Army, was called “Exercise Tocsin B†and it was the last of three national “Tocsin†survival exercises between 1960 and 1961. Exercise Tocsin B was the largest and most widely publicized civil defence drill to have ever been held in Canada. The drill simulated how provinces would warn Canadians if a nuclear attack on Canada was detected. By raising popular awareness of the potential for a devastating nuclear attack, Tocsin B showed what was at stake during the Cold War and demonstrated how the government would continue to operate during a time of crisis.

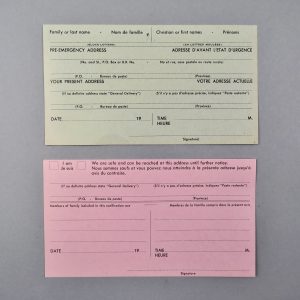

Emergency Postcards, Diefenbunker Museum: 2013A.001.0120.37, 2013A.001.0120.38

Federal government services were set to continue during the Cold War, with the intention of reaching each community through the postal network. One service in particular that was designed to aid in communication efforts across the country was the stockpile and distribution of postcards. Two postcards were intended to help coordinate survival efforts — a blue Emergency Change of Address Postcard to ensure that those whose homes were destroyed would still receive federal social services such as family allowance cheques, and a pink Safety Notification Postcard that allowed the evacuee to inform concerned family and friends that they had survived a nuclear attack. Both of these postcards from the Diefenbunker’s collections are double-sided, bilingual, and contain information such as instructions, pre-paid postage, and a section to fill in place of residence. The back of the blue postcard has sections designated to be filled out with the user’s pre-emergency address, present address, as well as names and a signature. The back of the pink postcard has two checkboxes to distinguish individuals versus a group, room to list members of the family, as well as fields for a date, time, and signature.

Exercise Tocsin B was met with controversy and the lessons learned were a matter of debate. When 500 air raid sirens were tested across the country, several mishaps revealed problems with the technology and gaps in the alert coverage. It became evident through this exercise the challenges of maintaining intergovernmental coordination if a nuclear attack were to destroy much of Canada’s communication and transportation infrastructure. Soon after this exercise, the Diefenbunker in Carp was completed. This site offered an emergency headquarters for Federal officials, which was closer than Camp Petawawa. It would have also allowed for the continuity of government if a nuclear attack on Canada was detected during the Cold War.

Though their effectiveness was never tested like the air raid sirens in Exercise Tocsin B, these two emergency postcards in the Diefenbunker’s collections are a reminder of the extensive preparations the government put in place to communicate with citizens and plan for our preparedness and subsequent survival in the event of a nuclear attack.